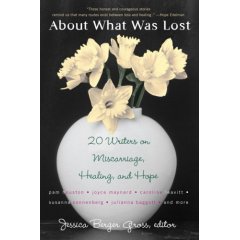

About What Was Lost

I live in a bubble. It shimmers in the sun and casts pale rainbows on everything I see: my husband, my two sturdy boys, our life together. Most days, I carry on as if the bubble’s not so fragile, but of course every once in a while, something I read or something I see will remind me that this is a very delicate state in which to live. It’s not, in fact, real. I can’t close myself off from the sadness of the world with walls of soap, because if I did, I’d be closing myself off to some real joy, too.

I live in a bubble. It shimmers in the sun and casts pale rainbows on everything I see: my husband, my two sturdy boys, our life together. Most days, I carry on as if the bubble’s not so fragile, but of course every once in a while, something I read or something I see will remind me that this is a very delicate state in which to live. It’s not, in fact, real. I can’t close myself off from the sadness of the world with walls of soap, because if I did, I’d be closing myself off to some real joy, too.

I was reminded of this reading the new anthology edited by Literary Mama columnist Jessica Berger Gross, About What Was Lost: Twenty Writers on Miscarriage, Healing, and Hope. When I mentioned to a friend that I was reviewing the book, she asked, “Why? Why would you choose to read something so sad?” Why, indeed? I’ve never been touched closely by miscarriage, why sign up to read about an experience I’ve managed, so far, to skirt?

Because I didn’t expect that the book would be only and irrevocably sad (and it is not). Because I expected to find in the book some beautiful, deeply-felt writing (and I did). Because miscarriage is hushed-up—although twenty to twenty-five percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage, did you know that? (I didn’t)– and I wanted to do some small thing to speak up about miscarriage. Because miscarriage is something that happens to women and families, and they grieve, and then learn how to carry their grief along as they move on in life. I wanted to read about that.

I read about the secrecy in which we shroud miscarriage, still, even though we know it happens so often. David Scott writes ruefully, “The world of miscarriage was a secret society we’d joined by accident, by living.” Emily Bazelon takes some small comfort in this, that this unwanted experience has moved her into a quiet community: “As I unraveled—there was a long time when I didn’t think about anything else—I held on to the idea that I was joining a sad but wise tribe.”

I read about the physical pain of miscarriage, its terrible perversion of labor. Jessica Jernigan’s doctor tells her that miscarrying will feel like bad menstrual cramps (which by now we should all know is a lame euphemism for tearing agony); instead, she writes, “It was much worse, and each time the pain came, I felt the urge to push, and this travesty of labor was worse than any physical hurt…. The doctor had also told me that I wouldn’t recognize anything resembling a baby. He wasn’t quite right about that, either…I recognized the gestational sac when I saw it…I held it in the palm of my hand. It was small and round and dark, like a plum.”

I read good ideas for helping women and their families endure miscarriage. Joyce Maynard reminds us to just, please, take it seriously. “However it occurs, under whatever circumstances…it is a death, and nothing less. It leaves you one child short, once again.” Dahlia Lithwick recalls the end of her pregnancy in the hospital’s labor ward, and comments bitterly, “I’d have preferred to have that surgery in a hospital broom closet or the damned parking lot. In hindsight, it’s unbelievable that any modern American hospital would not have a soothing, non-ironic place to minister to the thousands of pregnancies that end as mine did.” And so she suggests simply “that hospitals, which thoughtfully offer massages and hot tubs and music for the new mommies, could also provide spaces—both physical and psychological—for the almost-mommies as well.”

I read about the aftermath of loss, and the need to carry on for one’s family, as in Sylvia Brownrigg’s wrenching story of a trip to Lake Tahoe to memorialize her son Linnaeus: “As with so much of our experience with Linnaeus, my husband Sedge and I were accompanied by our son, Samuel, not yet two, and my stepson, Henry, seven. There was a certain need to keep up appearances… It’s a funny kind of family vacation, a trip that’s part fun and frolics in the snow, part ash-scattering.”

And I read about moving on. Susan O’Doherty’s “The Road Home” concludes the collection with her intertwined stories of becoming a mother after many losses and resuming a writing career. After reading to her son’s class, she writes, “A serious-looking girl raises her hand. You’re a mother, and you’re a writer,” she says.

I wait for her question, but there doesn’t seem to be one.

“That’s right,” I say.

She nods. “That’s good.”

I nod, too. “Yes,” I say. “It is.”

Thank goodness for all of these writers, sharing their stories and offering understanding sympathy to people grieving miscarriage. They map out a sad terrain, but suggest, too, some routes toward hope.