Saturday started like any other day. Eli came thumping down the hall at first light and climbed into bed with his patch blanket and blue bear for a wriggly cuddle. “Is it a school day?” he asked after a bit. “No, sweetie, it’s not,” I answered. “That means I can watch a show!” he crowed. So he jumped and I hauled myself out of bed and downstairs we went, where he settled on to the couch with his “show snack” of dry cereal and a sippy cup of milk. I turned on the TV, ready to read him the titles of the 26 episodes of Oswald we’ve recorded for him to choose from for his weekend morning’s entertainment.

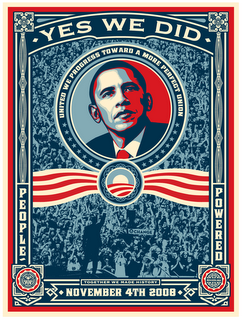

But before I could get to the Tivo screen, there was Hillary Clinton, bowing out of the race for president, and I sat back down on the couch, momentarily deflated.

“Mama?” Eli asked after a moment, puzzled that his beloved blue octopus wasn’t yet on screen. “Mama, please tell me the choices?”

“Just a minute, sweetheart; I want to watch this. This is very important.”

Soon Ben and Tony were downstairs, too, and we all watched the speech: Eli, bored and impatient, Tony providing running commentary to Ben (who’s been an easy Obama supporter ever since his kindergarten teacher put a campaign sign on the classroom door), and me with surprised tears in my eyes. Because despite my ambivalence about Clinton as a candidate, I found myself profoundly sad to see her candidacy end. Her candidacy – despite the terribly sexist coverage it attracted – put an end, finally, to the question of whether, as Gail Collins put it, “it’s possible for a woman to go toe-to-toe with the toughest male candidate in a race for president of the United States. Or whether a woman could be strong enough to serve as commander in chief.” Her candidacy made it clear that a women, indeed a mother, could govern the United States, and it inspired me.

Happily, I have plenty left to be inspired by. I can support an exciting candidate for president, and I can dive into lots of terrific reading in the wonderfully timely and engaging The Maternal Is Political. Now, I should admit that I am a completely subjective reader: many of the contributions in this anthology are by excellent writers whom I consider friends, women I know from my work at Literary Mama. And the book is edited by my fabulous partner in the work of managing the site, Shari MacDonald Strong. But, despite my subjectivity, I’m still a very critical reader; I’ve probably read over a dozen anthologies in the last year alone, and having now edited one myself, I’ve formed strong opinions on aspects ranging from cover design to essay length to a book’s organization.

You can all judge for yourselves what a great cover The Maternal Is Political has; the book gets other little things right, too. It offers reader-friendly sections, titled Believe, Teach and Act – words that move me, that get me thinking about the ways that I believe, teach and act just by reading them. It offers a reader-friendly variety of essay length and tone, from the 2 ½ page day-in-the-life account from Benazir Bhutto (reading how competently she moved through a day of governing and mothering made me mourn her all over again) or Cindy Sheehan’s sharp critique of the progressive left in “Good Riddance, Attention Whore,” to the more leisured reflection of Shari MacDonald Strong’s thoughtful “Raising Small Boys in a Time of War” or Barbara Kingsolver’s funny, smart “A Letter to My Daughter at Thirteen.”

And with all this writing, The Maternal Is Political gets the big thing right, too. It’s great writing, cover to cover. It’s all here–gender politics, sexual politics, school politics, adoption politics, religious politics, body politics, community politics, family politics, social politics—but with a mix of tone and approach that makes the book a real pleasure to read. Rather than weighing you down with the utter importance of it all, these writers make you want to think critically, get up off the couch, make a phone call, sign a petition. Do good in the world, and teach your children how to do good, also.

And that part’s not so hard, really. These essays remind us that our children are our constant witnesses, and so why not take subtle advantage of that while they’re young, as in Gayle Brandeis’ “Trying Out,” or in Jennifer Graf Groneberg’s quietly forceful “Politics of the Heart,” which relates moving through a regular day with her three children while following the news of a state assembly bill that would affect her ability to home school them:

At noon, another email update from MCHE arrived, explaining that the crowd had moved to the Capitol. I fed Carter a grilled cheese sandwich, and I fed the babies pears and green beans and bits of Ritz crackers in their high chairs, thinking about how flimsy my position felt—I was fighting for the right to educate my son, but I had nothing to go on but a mother’s intuition, a mother’s love.

In some of the essays, the children taught are sometimes older, and sometimes not the writer’s own. Amy L. Jenkins, in “One Hundred and Twenty-Five Miles,” describes how she took advantage of the confined space of a road trip to work on a young man’s views of gender roles. In Gigi Rosenberg’s “Signora,” she speaks up, in halting Italian, to break up a charged moment on a bus, and Anne Lamott wonders briefly if she’s gone too far, but is then reassured: “During the reception, an old woman came up to me and said, “If you hadn’t spoken out, I would have spit,” and then raised her fist in the power salute. We huddled for a while and ate M&Ms; to give us strength. It was a communion for those of us who continue to believe that civil rights and equality, and even common sense, may somehow be sovereign one day.”

All of these women write about families, but I was especially moved by stories of creating families, or asserting them in the face of challenges. I teared up at the end of Kathy Briccetti’s wonderfully rich detailing of her family’s complicated adoption history, which culminates in one of California’s first second-parent adoptions. And Ona Gritz, who writes a gorgeous monthly column for Literary Mama, writes matter-of-factly about the casual discrimination she faces every day:

Here is what I want to believe. That Lois didn’t think blond, blue-eyed Ethan and I were related because of my dark hair and eyes. Or that I look too young to be the mother of a two-year-old (even though I’m thirty-six). But there is another, more likely explanation, and I can feel myself squelch it down. To Lois’s mind, a disabled woman can’t be a mother. The disable are dependent and asexual. They are like children themselves.

I cannot stop thinking about the striking image of street children in Violeta Garcia-Mendoza’s poetic yet also clear-eyed account of a trip to Guatemala to adopt her first child:

I don’t expect the street children to whisper. I don’t expect them to approach us like they do, bumping against each other somnolently, like fish. Opening and closing their hands instead of their mouths. Some of them hold hands with a smaller

sibling, tethering themselves together to make sure they don’t get separated in the crowd. They try out a handful of English words on us—”hello,” “please”—before they learn I speak Spanish. Then they ask for money for milk, for medicine. Their skin is dull, inflamed in places, their lips chapped, hair tangled and matted; their feet are bare. They don’t swarm but quietly press against us with their soft por favores and gracias.

And finally, I come back again and again to the strong and simple words of Shari MacDonald Strong’s introduction: “…If my life as a mother of three children has taught me one thing, it’s that there is no more powerful act than mothering. There is no greater reason than my children for me to become politically involved, and there is no more important work to put my efforts to than those things that will make this world a better, safer place for my kids.” “Vote Mother,” Shari writes; indeed. Share this with the mothers you know, and their partners, friends, and children, and remind them: it’s time to get political.

For more reviews, plus an interview with Shari MacDonald Strong, check out MotherTalk this week.