I’m a Hip Mama, now

Check out my little essay, The Cookie, at the fabulous Hip Mama!

Posts tagged ‘writing’

Check out my little essay, The Cookie, at the fabulous Hip Mama!

This month’s Literary Reflections essay first came to me as a submission for the book I’m co-editing, Mama, Ph.D. I was torn when I read the essay: the writing knocked me out, but it didn’t particularly address the writer’s academic career. Happily, Julia co-wrote another essay for the book, and I got to use this for Literary Reflections. Here’s a long blurb:

When people asked me when I planned to get pregnant, I used to say, “After my first book.” I’d chosen to put my energies elsewhere, and I figured publication was such a long shot that I’d have plenty of time to live and write in peace. When a book came and a few people remembered that promise, I had to think fast. “After a second book,” I replied, ridiculous. I know Harriet Beecher Stowe wrote Uncle Tom’s Cabin at the kitchen table after her children were tucked in bed, and I imagine that people learn much about life as their children grow. Somehow, though, I still carry the old notion that negotiation is impossible, that a woman must be completely given over to one or another kind of work, and that if her attention ever wavers, terrible things happen.

This message comes from as far back as my first memory, which is little more than a few frozen images. I’m three years old, out behind a farmhouse in Turbotville, Pennsylvania, under a fir tree. The boughs are so thick that the grass is stunted, and long cones like corn cobs clutter the ground. Wandering between them, I see my oxblood, buckle shoes with little cut-out daisies on the toes. I don’t know what I’m doing out here after supper; my dad and older brother are elsewhere; Mom is at work. As I wander toward the place where the lawn drops down a steep bank to the road, I see fields and the next farm’s corn crib on the other side. Something over there rustles the tall grass: Sally Ann, my cat, stalking a field mouse? Suddenly she darts down the bank and, without looking, without thinking, I dash toward her.

Then I see the rounded front of a 1950s sedan, hear a loud screech, and see sky, although I cannot say in what order. Mostly I recall the sky and one red shoe flying against it for a long, long breath.

My eyes open. Stretched out on the grass beneath the branches, I see my father’s face, feel him touch my cheek, my shoulder, “Jules, Jules…” He is more distressed than I have ever seen him. Is he angry with me for crossing the road alone or for losing my shoe? Another strange man stands nearby; later I will learn that he is rushing to the hospital, where his wife is giving birth. The man and my father say “Geisinger” and “ambulance,” but I know I am fine. At the emergency room, I obey the white-coated men who ask me to follow their fingers with my eyes, and I hold still while they take X-rays, but all the while I know it is pointless. I can’t understand why the adults keep saying I am such a brave girl. What this first memory means, I now believe, is that even though enormous things may hit me sometimes, I’ll be OK in the end, and mercifully I’ve always known this in some small, strange way.

But when my mother tells this story, she starts by saying, “The first night I went back to nursing…” For her, it is a story about neglect and what happens when a mother isn’t there to watch her children.

Read the rest of “Fine: On Maternity and Mortality” here at Literary Mama.

A disclaimer: I’ve never been to a speed dating event. By the time I was leaving school and the prospect of having to look outside the classroom for a date presented itself, I was saved by a friend who fixed me up with Tony. End of story.

But I’ve heard about speed dating, where a large room’s set with many tables, a potential partner seated at each. An MC holds a timer, and you hop from table to table, talking to the occupant for a short time, until the timer goes off. You move on, and at the end of the event submit a request for phone numbers from the tables where you spent a nice 5 minutes.

Or so I hear.

I got a taste of this the other night, at a mixer for faculty and students at my new summer job, advising MFA students. I am looking forward to the work (my first paid work since Ben was born!); it seems the ideal kind of teaching, working closely with one student while s/he writes a thesis.

But how to match students with their summer advisors? In the past, the department chair did it, knowing her students and faculty well, balancing her talents for teaching and match-making in an elaborate calculus. This year, with a bigger group of summer advisors, she decided to let us play a more active role. The advisors were all required to submit profiles and pictures ahead of time, for the students to review. Some of the students were clutching these sheets as they roamed the room at the mixer. They were wearing name tags that identified their chosen genres: Non; Short; Long; Poetry. It took me some time to figure it out (Non, for Nonfiction: hey, that’s me! Short and Long for the fiction writers; apparently the poets just write poetry, no need to identify by form or length), and I spent the first half hour moving from group to group, trying to find my people. Eventually I found a small cadre of Nons and sat down to talk: a 3rd grade teacher writing essays about her work; a woman writing about her nephew’s traumatic brain injury; a stay-at-home mom writing a memoir. Maybe one of them will choose me? I’ll have to wait and see if anyone asked for my number.

Deborah Bacharach is your average doting mother. Of her baby girl, she writes, “Rose is gorgeous, courageous, and clever, and she can say “uh oh” with great aplomb…”

As a writer, Bacharach not only finds material in her darling daughter, but she finds a way to harness her sleep deprivation, the bane of every new parent: “Sleep deprivation makes me miserable, but it’s had two unforeseen advantages for my writing life: aphasia and visions.”

Read more about the inspirational power of sleep deprivation in this month’s Literary Reflections essay, “Fire, Aphasia and the Spirit World.”

I live in a bubble. It shimmers in the sun and casts pale rainbows on everything I see: my husband, my two sturdy boys, our life together. Most days, I carry on as if the bubble’s not so fragile, but of course every once in a while, something I read or something I see will remind me that this is a very delicate state in which to live. It’s not, in fact, real. I can’t close myself off from the sadness of the world with walls of soap, because if I did, I’d be closing myself off to some real joy, too.

I live in a bubble. It shimmers in the sun and casts pale rainbows on everything I see: my husband, my two sturdy boys, our life together. Most days, I carry on as if the bubble’s not so fragile, but of course every once in a while, something I read or something I see will remind me that this is a very delicate state in which to live. It’s not, in fact, real. I can’t close myself off from the sadness of the world with walls of soap, because if I did, I’d be closing myself off to some real joy, too.

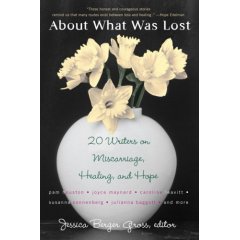

I was reminded of this reading the new anthology edited by Literary Mama columnist Jessica Berger Gross, About What Was Lost: Twenty Writers on Miscarriage, Healing, and Hope. When I mentioned to a friend that I was reviewing the book, she asked, “Why? Why would you choose to read something so sad?” Why, indeed? I’ve never been touched closely by miscarriage, why sign up to read about an experience I’ve managed, so far, to skirt?

Because I didn’t expect that the book would be only and irrevocably sad (and it is not). Because I expected to find in the book some beautiful, deeply-felt writing (and I did). Because miscarriage is hushed-up—although twenty to twenty-five percent of pregnancies end in miscarriage, did you know that? (I didn’t)– and I wanted to do some small thing to speak up about miscarriage. Because miscarriage is something that happens to women and families, and they grieve, and then learn how to carry their grief along as they move on in life. I wanted to read about that.

I read about the secrecy in which we shroud miscarriage, still, even though we know it happens so often. David Scott writes ruefully, “The world of miscarriage was a secret society we’d joined by accident, by living.” Emily Bazelon takes some small comfort in this, that this unwanted experience has moved her into a quiet community: “As I unraveled—there was a long time when I didn’t think about anything else—I held on to the idea that I was joining a sad but wise tribe.”

I read about the physical pain of miscarriage, its terrible perversion of labor. Jessica Jernigan’s doctor tells her that miscarrying will feel like bad menstrual cramps (which by now we should all know is a lame euphemism for tearing agony); instead, she writes, “It was much worse, and each time the pain came, I felt the urge to push, and this travesty of labor was worse than any physical hurt…. The doctor had also told me that I wouldn’t recognize anything resembling a baby. He wasn’t quite right about that, either…I recognized the gestational sac when I saw it…I held it in the palm of my hand. It was small and round and dark, like a plum.”

I read good ideas for helping women and their families endure miscarriage. Joyce Maynard reminds us to just, please, take it seriously. “However it occurs, under whatever circumstances…it is a death, and nothing less. It leaves you one child short, once again.” Dahlia Lithwick recalls the end of her pregnancy in the hospital’s labor ward, and comments bitterly, “I’d have preferred to have that surgery in a hospital broom closet or the damned parking lot. In hindsight, it’s unbelievable that any modern American hospital would not have a soothing, non-ironic place to minister to the thousands of pregnancies that end as mine did.” And so she suggests simply “that hospitals, which thoughtfully offer massages and hot tubs and music for the new mommies, could also provide spaces—both physical and psychological—for the almost-mommies as well.”

I read about the aftermath of loss, and the need to carry on for one’s family, as in Sylvia Brownrigg’s wrenching story of a trip to Lake Tahoe to memorialize her son Linnaeus: “As with so much of our experience with Linnaeus, my husband Sedge and I were accompanied by our son, Samuel, not yet two, and my stepson, Henry, seven. There was a certain need to keep up appearances… It’s a funny kind of family vacation, a trip that’s part fun and frolics in the snow, part ash-scattering.”

And I read about moving on. Susan O’Doherty’s “The Road Home” concludes the collection with her intertwined stories of becoming a mother after many losses and resuming a writing career. After reading to her son’s class, she writes, “A serious-looking girl raises her hand. You’re a mother, and you’re a writer,” she says.

I wait for her question, but there doesn’t seem to be one.

“That’s right,” I say.

She nods. “That’s good.”

I nod, too. “Yes,” I say. “It is.”

Thank goodness for all of these writers, sharing their stories and offering understanding sympathy to people grieving miscarriage. They map out a sad terrain, but suggest, too, some routes toward hope.

This month in Literary Reflections, Amy Mercer remembers how she loved solitude as a child, and describes how she longs for it now as a mother and writer:

But now, married for almost ten years and the mother of two children, I fear I’ll never be alone again. I check email with a child on my lap. I cook dinner with a boy on the ladder next to me, making “salt and pepper make-up” (water, flour, salt and pepper) in a mixing bowl. I shower with my two year old, shampooing with one hand. I carry a boy on each hip to bed, where we read, cuddle, get more “choco” (chocolate milk), and when I tuck them in for the third time, I’m weary of others. Collapsing onto the couch with a magazine or a book, I read someone else’s story. I am alone at last for as long as I can stay awake.

Someone else’s story reminds me of my own. Alone with my children, I banish them to their playroom, so I can write. I let them play computer games for too long, so I can write. I buy them new DVD’s, so I can write. Will asks for a snack while I struggle for the right word, and Miles pulls on my arm as I type. Alone in motherhood; in the hours of laundry and cleaning and cooking and telling everybody else what to do, I am connected to the rest of the world when I write. With Play-Doh spread across the table, Will cutting and Miles eating, I write about trying to relax. As they eat dinner at the kitchen counter, I write about the McDonald’s commercials, and my struggle to keep our family healthy. While the boys take a bath, splashing water across our new tile floor, I write about my definition of home. After I read them books, I sneak out of their room, and if I’m not too tired, I write about giving birth to readers.

Read more about how Amy Mercer plays Solitaire.

I was so sad to emerge from my flu haze this morning to learn that Molly Ivins has died. Her writing offered the very best combination of smart and funny. The best way to memorialize her, I think, is to keep on writing against the war in Iraq.

From her last column:

The purpose of this old-fashioned newspaper crusade to stop the war is not to make George W. Bush look like the dumbest president ever. People have done dumber things. What were they thinking when they bought into the Bay of Pigs fiasco? How dumb was the Egypt-Suez war? How massively stupid was the entire war in Vietnam? Even at that, the challenge with this misbegotten adventure is that we simply cannot let it continue.

…We are the people who run this country. We are the deciders. And every single day, every single one of us needs to step outside and take some action to help stop this war. Raise hell. Think of something to make the ridiculous look ridiculous. Make our troops know we’re for them and trying to get them out of there.

Rest in peace, Molly Ivins.

I was recently asked to write the story of Eli’s birth for my doula. She’s an accomplished photographer, assembling a book of birth photos and stories. It was a nice project for me; I’d written quite a bit in my journal about the day, but fleshing it out into an essay, with feedback from my writing class, was a terrific writing experience.

But after I wrote it, I thought, how much of this is true? What I remember of the day now is what I wrote in my journal a week or so after the fact, by which point some details were probably already lost. When did I start turning the day into a story? While it was still happening? I don’t think I had the wherewithal for that, actually. I do get through a lot of stuff by thinking about the story it will make later, but not labor! But it did start to become a story before I even started telling people about the day, while Tony and Britt and I were all still huddled around brand-new Eli, marveling about our experience. And then I started telling people about it, and then I wrote it down, and now I’ve written it again, and, and, and…

I thought about this particularly because after I wrote this latest version of Eli’s birthday, I gave it to Tony to read, and wondered how much of it he’d remember, or even agree with. But he’s an excellent partner to a writer, knowing that whatever I write is my truth. He can write his own version if he wants.

This is all a lengthy lead-in to a quote that struck me from Julian Barnes’ essay in a recent New Yorker:

My brother remembers a ritual—never witnessed by me—that he calls the Reading of the Diaries. According to him, Grandma and Grandpa each kept diaries, and in the evenings would sometimes read out loud to each other what they had recorded five years earlier. The entries were apparently of stunning banality but frequent disagreement. Grandpa would propose, “Friday. Fine day. Worked in garden. Planted potatoes.” Grandma would reply, “Nonsense,” and counter-cite, “Rained all day. Too wet to work in the garden.”

I just love this. Love picturing the old and crotchety pair reading to each other from their diaries (diaries like my father keeps, of weather and garden reports). Love that they both keep diaries. Love that they disagree! It just cracks me up.

Barnes goes on:

My brother also remembers that once, when he was very small, he went into Grandpa’s garden and pulled up all his onions. Grandpa beat him until he howled, then turned uncharacteristically white, confessed everything to our mother, and swore that he would never again raise his hand against a child. Actually, my brother doesn’t remember this, either the onions or the beating; he was just told the story repeatedly by our mother. And, indeed, if he were to remember it he might well be wary of it: he believes that many memories are false, “so much so that, on the Cartesian principle of the rotten apple, none is to be trusted unless it has some external support.” I am more trusting, or self-deluding, however, so shall continue as if all my memories were true.

And so this is how I write. No, I’m not presuming to claim I write like Julian Barnes, just that I’ll write as if all my memories are true, and go from there.

This is from Annie Dillard’s The Writing Life, a wonderful book that I recently re-read:

Several delusions weaken the writer’s resolve to throw away work. If he has read his pages too often, those pages will have a necessary quality, the ring of the inevitable, like poetry known by heart; they will perfectly answer their own familiar rhythms. He will retain them. He may retain those pages if they possess some virtues, such as power in themselves, through they lack the cardinal virtue, which is pertinence to, and unity with, the book’s thrust. Sometimes the writer leaves his early chapters in place from gratitude; he cannot contemplate them or read them without feeling again the blessed relief that exalted him when the words first appeared—relief that he was writing anything at all. That beginning served to get him where he was going, after all; surely the reader needs it, too, as groundwork. But no.

Every year the aspiring photographer brought a stack of his best prints to an old, honored photographer, seeking his judgment. Every year the old man studied the prints and painstakingly ordered them into two piles, bad and good. Every year the old man moved a certain landscape print into the bad stack. At length he turned to the young man: “You submit this same landscape every year, and every year I put it on the bad stack. Why do you like it so much?” The young photographer said, “because I had to climb a mountain to get it.”

There’s an essay I’ve been writing, off and on, for about three years now. I realize that I’m hanging on to sections of it just because I’m used to them, they have Dillard’s “ring of the inevitable.” I’m not sure they have much place in the essay anymore. They served a useful purpose for me–they got me to the more interesting place in the essay that I am now–but I don’t think the reader needs them. Time to set them aside and dive back in.

It didn’t hit me when, after seventeen hours of mostly calm and gentle labor, my baby, the child I was thinking of as Charlotte (or maybe Josephine), burst out with a splash, my waters breaking with the head’s emergence. I heard my doula exclaim, “Look at him!”

It didn’t hit me when Ben came to visit us in the hospital the next morning. I couldn’t take my eyes off my first born, so suddenly grown-up next to his baby brother, so proud in the button-down shirt Tony had chosen for the occasion. Ben didn’t even glance my way; he went straight for the plastic terrarium and hovered his hand over Elijah’s soft head, unsure about touching this unfamiliar creature.

It didn’t even hit me the day I was changing Eli’s diaper on the bathroom floor while Ben was sitting on the toilet, and Eli took advantage of the diaperless moment to shoot a pale fountain in the air, and Ben started laughing so hard he missed the bowl and oh, it all hit me. But it didn’t hit me.

It didn’t hit me until Tony and I went to see The Squid and The Whale (Noah Baumbach, 2005), several weeks after Eli’s birth. Watching the film’s mom talking to her boys, calling one Pickle and the other one Chicken, I leaned over to Tony and whispered, “Hey! I’m the mother of sons.” And Tony gave me a look that said, “Well, duh!” and ate another piece of popcorn.

Read more about The Squid and The Whale in my column at Literary Mama.