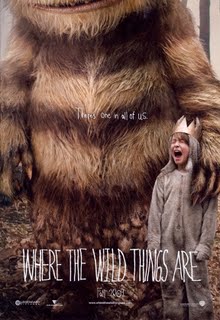

Where the Wild Things Are

A lifetime ago, when I lived in Manhattan, I worked for a literary agent who specialized in children’s book writers and illustrators; his clients’ books now fill my kids’ shelves. Initially, I was hired to read manuscripts that came in from potential clients, and to help the subsidiary rights agent handle the contracts for foreign publication of our clients’ books.

But the job I aspired to, and the job I eventually earned, was handling permissions. Anyone who wanted to use one of our client’s illustrations on a greeting card or a t-shirt, or wanted to quote some lines from their books in their newspaper article or dissertation, first had to call me, and I would work out the details with the writer or illustrator. It was fun to talk to our clients of course, but it was fun, too, to talk to folks who had interesting ideas about how to use their work, and I was always glad when I could help make an agreement.

Among the many artists we worked for, Maurice Sendak was the one whose work is in such high demand that I got to speak to him by phone every day. The office didn’t have email at the time, and we only used faxes for overseas communications. We all wished sometimes that there was a quicker way to conduct this business, some way that didn’t involve both parties being available at the same time, but I knew that I was really lucky to be making these phone calls to Mr. Sendak.

There was a prescribed time of day to make the call– just after lunch, as I recall, though I could be mistaken about that–and I always had my notes about each permission request typed up clearly so that I could be really efficient on the phone. I understood that he had more interesting things to do and I didn’t want to waste his time. There were some requests that never reached his ears; every month, it seemed, some fraternity would ask permission to make and sell “Delta Chi, Where the Wild Things Are!!!” t-shirts. I’m sure plenty of fraternities made such shirts anyway, but if they thought to ask permission, we had to turn them down.

I suppose he could have issued a blanket No for all uses of his work and never even bothered with us. But he didn’t do that. In those pre-caller ID days, he screened his calls, so I would begin talking, introducing myself and starting in with the first request, and hoping that he would pick up. One of the first times I called, I made the mistake of mentioning another artist who was going to be included in the project, one Sendak felt had copied his work, and he picked up the phone only to utter a short, withering “No” before hanging up. Or there was the time he commented, about a request that I have since blocked, “I would rather chew glass.” But most of the time, I had vetted the requests well enough that they interested him, and he’d ask probing questions about them and sometimes I’d be talking to him long enough that I could stop being distracted by the excited little voice in the back of my head that was always saying, “You’re talking to Maurice Sendak!”

So, all of this is a very lengthy preamble to the fact that when I first heard, years and years ago, that a movie was being made of Where the Wild Things Are, I didn’t believe it. I’d seen proposals come and go and although they very moved quickly off my desk and on to the desks of more important people, they never went very far beyond that. But I kept hearing about this movie. And then I heard that Spike Jonze and Dave Eggers were involved, and I began to believe it was really happening. Also, I knew it would be good. Not just because I think Jonze and Eggers are the right guys for the job (though I really, really do. I mean, come on; Spike Jonze made Adaptation. Obviously he was going to do something interesting with this book). No, mostly I knew it would be good because if Maurice Sendak was letting it happen, he clearly trusted that his book was in good hands.

I saw the movie early, as a benefit for Dave Eggers’ 826 Valencia, and I haven’t stopped thinking about it. It is not a kids’ movie, or at least not a movie for kids who are still reading the book; kids who have outgrown the book might think the movie is too young for them, but convince them that they are wrong and take them with you. I don’t want to give anything away here now, so will say only that they have expanded on the story in good and moving ways. The actors, from Max Records as Max to Catherine Keener as his mom, to the amazingly-cast actors who voice the Wild Things (Catherine O’Hara, Forest Whitaker, Paul Dano, Chris Cooper, Lauren Ambrose and James Gandolfini) are all fabulous. I am planning to go back to see it a few more times, if only just to hear the heart-breakingly wistful note in James Gandolfini’s voice when he says to the other Wild Things that he just wants to sleep in a real pile.

But here, don’t take my word for it. Hear what Sendak himself has to say about the film.