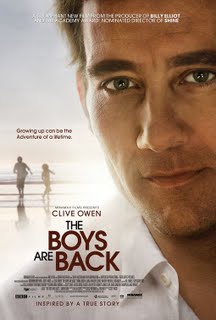

The Boys Are Back

Why would I spend an evening at a movie about a dad who’s left to raise his two sons alone after his wife dies of cancer? I’ve written before about absent-mother movies; it’s not that I have some morbid curiosity about families without mothers or expect that these movies are going to show me what might be (I certainly hope not!) I love movies about family relationships, I love quiet, talky movies, and I have to admit I love a chance to attend a free press screening. So I went to The Boys Are Back with a friend (whose own two boys are old enough to be left alone for a couple hours while she goes to an early evening movie). I thought, based on what I knew of the plot, that it might be a bit sappy. But we were both very pleasantly surprised, because The Boys Are Back is a really lovely film about a man learning how to father after his wife passes away.

The film is based on Simon Carr’s memoir of the same name. Carr is a columnist for The Independent, though in the film’s one significant, and perfectly reasonable, deviation from the memoir, Clive Owen plays him as a sportswriter named Joe. It makes his job look a bit more glamorous (we see him writing coverage of Michael Phelps at the Sydney Olympics), though my friend and I did wonder exactly how this dad was supporting his family’s very comfortable lifestyle on a newspaper writer’s salary. We should be so lucky. But that’s a tiny quibble in what’s otherwise a very realistic, human, and beautifully-told story about a little family struggling to regain its equilibrium after a devastating loss.

The film opens with Joe driving a jeep along the beach. Water is spraying past, and we begin to see that people are shouting at him, presumably just because he is driving on the beach. But then the camera pulls back and we see a little boy perched on the hood of the car, griping the windshield wipers behind him, screaming with delight. This is our first clue that this family is different. The film flashes back briefly then, to tell the story of the mother’s cancer diagnosis and death, and the moment I knew this was a film that understands a bit about children and families was when Joe tells his son, Artie (a sweet and impish Nicholas McAnulty) that his mom is ill. The four year-old has good questions: “Is Mummy going to die? When? Will she die by dinner time? Will she die by bedtime? Will she die by breakfast?” And Joe understands that these are reasonable questions from a kid, and answers honestly, “I don’t know.”

Most of the film then narrates the life Joe builds with little Artie and his son from his first marriage, Harry, a young teen who comes to live with them some months after the death of Artie’s mom. “The fact is,” explains Joe to Harry, “I run a pretty loose ship. . . . We found that the more rules we had the more crimes were created; petty prosecutions started to clog up the machinery of life. Conversely, the fewer the rules we had, the nicer we were to each other.” It’s not all indoor water balloon fights and bike-riding in the kitchen (though there is that); the silly, like in real life, is tempered by the serious, and it all adds up to a fine film about ordinary life.